An MVP pattern using scoped Dagger2 IoC containers

i have previously written about using dagger2 in my new project recommender. one of the things i found most frustrating about writing native android code in contrast to c# or javascript code is how hard it has been in the past to get a reasonable amount of test coverage from unit tests.

there have been challenges

- eclipse didn't have great support for testing

this has been addressed as androidstudio is much better at working with junit projects and androidstudio 1.4 now properly supports dagger2 and junit. - there were limited dependency injection frameworks

this has been helped with the release of dagger2 which proven to be reliable, flexible and fast dependency injection. there are also alternatives, dagger1 or roboguice are also viable options.

- test code either required an emulator or needed to be run on a device.

this made the tests slow and unreliable, either giving false results or crashing which made them useless

now that google has released a mock layer and roboelectric has provided a reliable mocking framework we can run tests in the desktop jvm and get reliable accurate results. - there haven't been many frameworks for isolating business logic from ui

in c# and javascript there are any number of patterns and frameworks to help isolation, such as ASP.NET MVC, Knockout, Angular etc. In Android development there have been few frameworks such as Mortar and Flow

While things have been getting better I still needed to settle on a framework for code isolation to give me a codebase structure that would lend itself to extensive unit testing. I did look at Mortar however I found it to be a little “all or nothing” meaning that retrofitting it to an existing codebase in an incremental manner was not going to be possible so I decided to look at as many examples as I could and to partition the code using my own lightweight framework. I have tried to reference all the articles I have read but if I have missed any then I apologise, this code is very much a distillation of may other peoples hard work.

Scoped containers

The first think needed are scoped IoC containers. There are some objects that we need only one of and we need them across the whole application, there are however other objects that we want a separate instance for each activity and we want them to go away when the activity goes away.

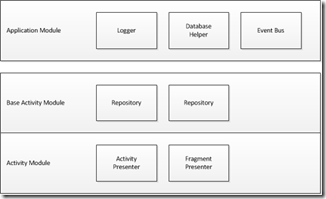

Dagger2 modules are the IoC containers I will be using. The application module contains global singletons that are used throughout the app, for example loggers. If activities are sufficiently simple they might only use an application module and they might not have their own activity module.

For more complex activities (which is most of them) we have an activity module, which will contain the presenters used by the activity. The activity module inherits from a base activity module that has all the data repositories as the repositories are needed by many activities. Don't get confused the base activity module is just a syntactic convenience – the repositories are not shared across activities, each activity has its own presenter and its own repositories, only objects in the application module are shared.

The Dagger2 code for an application module looks like this.

@Singleton // Constraints this component to one-per-application or unscoped bindings.

@Component(

modules = ApplicationModule.class

)

public interface IApplicationComponent {

// do not forget to list ALL classes that can ask to be injected

// remove any that do NOT use this component

void inject(OpenSourceLicensesActivity activity);

// fragments without a scoped component just use the application component

// we only need to put things in here that are exposed to subgraphs

Context context();

IEventBus provideEventBus();

}

@Module

public class ApplicationModule {

private final AndroidApplication application;

public ApplicationModule(AndroidApplication application) {

this.application = application;

}

@Provides

@Singleton

Context provideApplicationContext() {

return this.application;

}

@Provides

@Singleton

ILoggerFactory provideLogger(SlfLoggerFactory loggerFactory) {

return loggerFactory;

}

@Provides

@Singleton

SQLiteOpenHelper provideOpenHelper(RecommenderDatabaseHelper helper) {

return helper;

}

@Provides

@Singleton

IEventBus provideEventBus(RxEventBus eventBus) {

return eventBus;

}

}

Whenever Dagger supplies a dependency it will also supply all of its dependencies as so on. For example if the RxEventBus needs an ILoggerFactory Dagger will provide one, as long as the RxEventBus constructor is marked as @Inject. This process is automatic within the module however if any further derived modules, for example an activity module needs access to a ILoggerFactory then we need to make that available in the component interface.

The activity module is then written like this

@ActivityScope

@Component(

dependencies = IApplicationComponent.class,

modules = BaseActivityModule.class

)

public interface IBaseActivityComponent {

// things that need an activity scope component but dont have their own presenter

void inject(MainPreferencesFragment fragment);

// we only need to put things in here that are exposed to subgraphs

Activity getActivityContext();

// repositories should not be shared between different activities

// so we do not put it in the application component

IRecommendationRepository getRecommendationRepository();

}

@Module

public class BaseActivityModule {

private final Activity activityContext;

public BaseActivityModule(Activity activityContext) {

this.activityContext = activityContext;

}

@Provides

@ActivityScope

Activity getActivityContext() {

return this.activityContext;

}

@Provides

@ActivityScope

IRecommendationRepository provideRecommendationRepository(RecommendationRepository repository) {

return repository;

}

}

@ActivityScope

@Component(

dependencies = IApplicationComponent.class,

modules = {BaseActivityModule.class, EditRecommendationModule.class}

)

public interface IEditRecommendationComponent extends IBaseActivityComponent {

// list any activities or fragments that use this component

void inject(EditRecommendationActivity activity);

void inject(RecommendationEditFragment fragment);

// used by the tests

IEditRecommendationPresenter getFragmentPresenter();

IEditRecommendationActivityPresenter getActivityPresenter();

}

@Module

public class EditRecommendationModule {

/**

* this is the presenter used by the edit activity

*/

@Provides

@ActivityScope

IEditRecommendationActivityPresenter provideActivityPresenter(

EditRecommendationActivityPresenter presenter)

{

return presenter;

}

/**

* this is the presenter used by the edit fragment

*/

@Provides

@ActivityScope

IEditRecommendationPresenter providePresenter(

EditRecommendationPresenter presenter)

{

return presenter;

}

}

The EditRecommendationModule is just one of the modules used the application, other activities have their own module, however they all inherit from the base activity module as they all need access to common things, however as we said above they get their own instance of anything marked @ActivityScope, only the objects marked @Singleton are shared across the application. The inheritance is to avoid having to type out the declarations in the BaseActivityModule in each presenter module.

The BaseActivityComponent needs to declare any objects that are needed by the presenter in its component interface just like the ApplicationComponent. The PresenterComponent also exposes the two presenters, this is so that we can access them from the unit tests.

It might seem odd to have to declare inject() methods in the components for all the classes that can inject using the component. In other IoC frameworks this is not needed however Dagger2 is entirely done at compile time, there is no runtime reflection, and so we need to explicitly indicate to Dagger2 at compile time which classes inject which component so that the correct code can be generated.

The activity scope is just declared like this.

@Scope

@Retention(RetentionPolicy.RUNTIME)

public @interface ActivityScope {

}

The only other thing to remember is that we cannot mix and match all the objects in the application component must be @Singleton and all the components in the Activity component must be @ActivityScope

The presenter pattern

The presenter pattern I settled on is very simple and lightweight. It also means that more typical activities where UI and business logic and data access code is all mixed up can coexist with more formally laid out Model View Presenter activities.

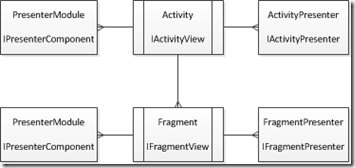

An activity that is complex would have this arrangement

The activity has an instance of the component and uses it to inject itself which will inject the presenter as well as any of the presenter’s dependencies. The activity may optionally create one or more fragments, which will in turn implement their own view interface and inject themselves to get their own presenter. The presenters are all isolated. If the activity presenter needs to perform an action on the fragment it must do so via the activity view interface.

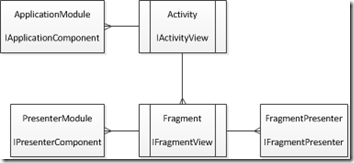

A simple activity that predominately contained UI could have a simpler structure, it can just access application global objects and not use a presenter at all. Simple activities can contain simple or complex fragments like this.

To try and encourage uniformity in the pattern the presenters and view interfaces have common bases like this.

public interface IPresenter{ void onCreate(); void onDestroy(); void bindView(V view); void unbindView(); }

The presenter lifecycle is that we call bindView as soon as the presnter is created and unbindView when the activity or fragment is going away, create and destroy enable the presenter to populate the view and release any resources or subscriptions.

public interface IView {

void end();

void showError(Throwable throwable);

void showMessage(int messageId);

}

It seemed like a reasonable presumption that all views (activities or fragments) would be able to end and show messages and errors.

Activity lifecycle

Android creates the activity classes for the application as a result of Intents declared in the manifest. To get everything setup the activity needs to get its component and then use it to inject itself which will create the presenter and all its dependencies.

The code usually looks like this

public class EditRecommendationActivity extends BaseActivity

implements

IEditRecommendationActivityView

{

private IEditRecommendationComponent component;

@Inject

protected ILoggerFactory logger;

@Inject

protected IEditRecommendationActivityPresenter presenter;

protected IEditRecommendationComponent getActivityComponent(Activity activity) {

if (component == null) {

component = DaggerIEditRecommendationComponent.builder()

.iApplicationComponent(getApplicationComponent())

.baseActivityModule(new BaseActivityModule(activity))

.editRecommendationModule(new EditRecommendationModule())

.build();

}

return component;

}

@Override

protected void injectDependencies(IApplicationComponent applicationComponent) {

// will inject into the base as well as this class

getActivityComponent(this).inject(this);

}

@Override

protected void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

injectDependencies(getApplicationComponent());

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

setContentView(R.layout.activity_edit_recommendation);

logger.getCurrentApplicationLogger().debug("EditRecommendation started");

presenter.bindView(this);

// unpack any parameters from the Bundle

// do any other UI init

fab.setOnClickListener(this);

presenter.onCreate();

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

logger.getCurrentApplicationLogger().debug("EditRecommendation.onDestroy()");

presenter.unbindView();

presenter.onDestroy();

super.onDestroy();

}

}

Its a bit unfortunate that this code needs to be present in each activity, its not possible at the moment to use Dagger2 to inject in the base class, though perhaps this will change in future.

The call to inject() will initialise the ILoggerFactory as well as the presenter, this is because we want the activity to be able to emit logging without having to go through the presenter.

The view also implements the basic IView operations

@Override

public void end() {

finish();

}

@Override

public void showError(Throwable throwable) {

Toast.makeText(this, throwable.getMessage(), Toast.LENGTH_LONG).show();

}

@Override

public void showMessage(int message) {

Toast.makeText(this, message, Toast.LENGTH_LONG).show();

}

As well as implementing its own specific set of operations via its own interface like this

public interface IEditRecommendationActivityView extends IView {

RecommendationType getRecommendationType();

void setMainTitleTextId(int id);

}

Activity presenter lifecycle

This is what this activity presenter looks like

public class EditRecommendationActivityPresenter

implements IEditRecommendationActivityPresenter

{

IEditRecommendationActivityView view;

@Inject

public EditRecommendationActivityPresenter() {

}

@Override

public void onCreate() {

setMainTitleForRecommendationType();

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

}

@Override

public void bindView(IEditRecommendationActivityView view) {

this.view = view;

}

@Override

public void unbindView() {

this.view = null;

}

In this example the activity is quite simple, as many Android applications much of the work is delegated to a fragment.

Fragment lifecycle

The fragment is created in the activity like this

RecommendationEditFragment editFragment = new RecommendationEditFragment(); editFragment.setArguments(recommendationType, recommendation, false); getSupportFragmentManager().beginTransaction() .add(R.id.fragment_container, editFragment, TAG_EDIT_FRAGMENT) .commit();

The lifecycle code of a fragment is similar to that of an activity.

public class RecommendationEditFragment extends BaseFragment

implements IEditRecommendationView

{

private IEditRecommendationComponent component;

@Inject

protected IEditRecommendationPresenter presenter;

private IEditRecommendationComponent getComponent() {

if (component == null) {

component = DaggerIEditRecommendationComponent.builder()

.iApplicationComponent(getApplicationComponent(getActivity()))

.baseActivityModule(new BaseActivityModule(getActivity()))

.editRecommendationModule(new EditRecommendationModule())

.build();

}

return component;

}

@Override

public void onCreate(Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

getComponent().inject(this);

final Bundle args = getArguments();

recommendationType = args.getParcelable(RECOMMENDATION_TYPE);

recommendation = args.getParcelable(RECOMMENDATION);

presenter.bindView(this);

}

@Override

public View onCreateView(LayoutInflater inflater, @Nullable ViewGroup container, @Nullable Bundle savedInstanceState) {

View view = inflater.inflate(R.layout.fragment_recommendation_edit, container, false);

ButterKnife.bind(this, view);

presenter.onCreate();

return view;

}

@Override

public void onResume() {

super.onResume();

if (!isInjected()) {

getComponent().inject(this);

}

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

presenter.onDestroy();

super.onDestroy();

}

The fragment uses the same component interface as the activity however it will receive its own set of objects and is completely isolated from the activity. If we wanted to share the components between the activity and the fragment then we could implement an interface in the activity to return the component and call that from the getComponent() method.

The fragment also implements is own specific interface so that the presenter can manipulate the UI.

public interface IEditRecommendationView extends IView {

Recommendation getRecommendation();

void copyToUi(Recommendation recommendation);

Recommendation getRecommendationFromUi();

RecommendationType getRecommendationType();

void hideBrowseButton();

}

Fragment presenter lifecycle.

The lifecycle of the presenter is similar to that of the activity presenter.

public class EditRecommendationPresenter

extends

BasePresenter

implements

IEditRecommendationPresenter {

private ILoggerFactory logger;

private IRecommendationRepository repository;

private Context context;

private IEventBus eventBus;

private boolean isFromShareReceiver;

@Inject

public EditRecommendationPresenter(

ILoggerFactory logger,

IRecommendationRepository repository,

Context context,

IEventBus eventBus)

{

this.logger = logger;

this.repository = repository;

this.context = context;

this.eventBus = eventBus;

}

@Override

public void onCreate() {

if (isFromShareReceiver) {

view.hideBrowseButton();

}

Recommendation recommendation = view.getRecommendation();

view.copyToUi(recommendation);

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

// stop any subscriptions

repository.close();

}

View implementation

The intention is that the view implementation should only deal with the UI and should not contain any business logic. We do not intent to write tests against the view logic.

@Override

public void hideBrowseButton() {

btnBrowse.setVisibility(View.GONE);

}

@Override

public void copyToUi(Recommendation recommendation) {

txtName.setText(recommendation.getName());

txtBy.setText(recommendation.getBy());

txtCategory.setText(recommendation.getCategory());

txtNotes.setText(recommendation.getNotes());

txtUri.setText(recommendation.getUri());

}

@Override

public Recommendation getRecommendationFromUi() {

Recommendation recommendation = new Recommendation();

recommendation.setName(txtName.getText().toString());

recommendation.setBy(txtBy.getText().toString());

recommendation.setCategory(txtCategory.getText().toString());

recommendation.setNotes(txtNotes.getText().toString());

recommendation.setUri(txtUri.getText().toString());

return recommendation;

}

This enables writing unit tests against the presenter contained business logic (which is completely isolated by injected interfaces)

If you want to see the complete source code, or grab the code and step through it then head over to bitbucket.